Give it a try!

|

DMA |

|

Unfortunately, the large diameter pieces from the first crop developed minute cracks and had poor color. Because of that, I thought I would never be able to boast of playing on bassoon cane grown in my back yard.

Then, I read an article published in the spring 1998 issue of the Leblanc Bell (G. Leblanc Corporation, Kenosha, Wisconsin) about the Marca cane plantation in the Var region of France. They cut their cane during the winter (December through February), set it upright on trestles until May, strip it, lay it horizontally, and turn it periodically to sun dry. I tried this process and solved the cracking problem. Evidently, by cutting the stalk in the winter in its dormant stage, the sap drained more completely.

Last spring, I took several stalks of my one-inch diameter cane to John Shamlian, retired Philadelphia Orchestra bassoonist, bassoon repairman, and reed maker. I have been very fortunate to have John close by to help me with mechanical bassoon problems and reed problems. I knew he had a gouger, which I didn’t, and I knew if anyone could make a good reed out of this cane, he could.

When we came back from our summer vacation that year, John had made four reeds from this cane. I noticed right away that they played well, but I hesitated to come to any conclusion. But, the more I went through the process of selecting a good reed, the more I realized that these backyard reeds were comparable to the best I had in my possession. They played extremes in dynamics, had a nice sound, and responded well.

Of course, after having used only a few reeds, the jury is still out. Perhaps I am psychologically playing these reeds better or imagining that they play better! However, at this point, I am very encouraged.

Assuming the cane is good, I have difficulty understanding why. The growing conditions in my back yard are only so-so. The topsoil is only six inches deep. Below that, the soil becomes very hard clay. The topsoil is sandy and drains well. That may be a plus. The New Jersey winters are not too harsh—not as good as the South but better than the North or Midwest. I have heard of arundo donax being grown in Indiana, and winters there can be quite harsh. So, maybe the plant can be grown most anywhere. I certainly didn’t think it would grow in New Jersey.

Two years ago, when we experienced a very mild New Jersey winter, the stalks leafed out again, the way, as I understand, they do in the Var region of France. Except for that one year, the leaves normally do not reappear the second summer in my locality. However, the quality of the cane hasn’t been affected either way.

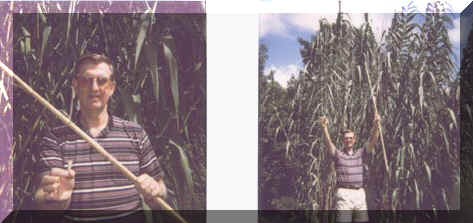

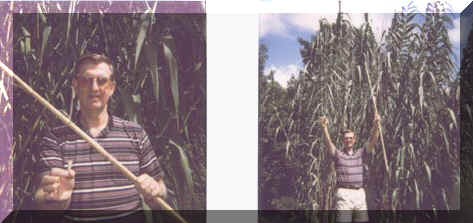

There is a considerable amount of variance in this “grass” made by Mother Nature. The diameter of the stalks will vary from nine millimeters to over an inch and grow from six to eighteen feet tall. The bottom of the stalk is too coarse and the top, too flexible. Only certain sections of the middle can be used. Also, there is the variation between tubes or sections. Many tubes are unusable because the stalk was bent. Most of the cane has to be thrown away for one reason or another. To find the correct cane diameter, color, and texture for a superior reed requires considerable care.

One advantage of growing your own cane is that you can participate in the earlier stages of the selection process. Most of us make reeds from cane that has been selected by someone else. I am sure most commercial cane is very good, but it’s not like selecting your own. Perhaps it’s like eating vegetables fresh from your own garden compared to buying them at the grocery store.

Why not grow your own arundo donax? At the very least, you will become familiar with Mother Nature’s plant upon which our lives and careers depend. For me, the whole experience has been a real trip. What started out as just a lark has developed into something beyond my wildest dreams—playing on a reed grown from my own backyard!

Give it a try!

(April, 2000 update: I performed a recital using my "backyard reed" and often use it to play the operas!)